Colorado, New York, and Vermont are among the states challenging the map, which will be used to direct $42.5 billion in federal funding

The new FCC broadband map lets you type in your address to see internet providers in your area.

By James K. Willcox

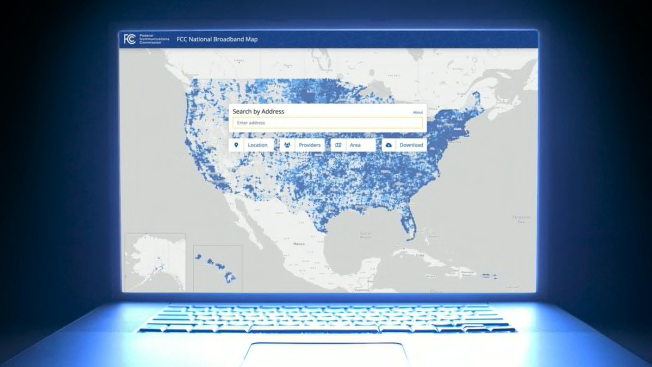

A few weeks ago, the Federal Communications Commission released a new national broadband map, which is supposed to help consumers see their options for internet service. Just as important, the map will be used to help determine where some $42.5 billion in federal funds will go to build out better access in places where high-speed, affordable broadband is lacking.

The map has quickly become a battleground for states, including Colorado, New York, and Vermont, which say it doesn’t accurately reflect how many of their citizens lack fast access to the internet. If the FCC map understates the problem, state officials say, they won’t get the funding needed to address the problem.

Despite arguments over the new FCC map, it’s widely acknowledged to be more accurate than the previous version. To judge for yourself, you can plug in your address—and let the FCC know if you find an inaccuracy.

"The not-so-well-hidden-secret for years has been that the FCC’s broadband maps were woefully inadequate and grossly overstated the number of households that have access to broadband," says Jonathan Schwantes, senior policy counsel at CR. "The new national broadband map is more accurate, but we still have a ways to go. With literally billions of dollars at stake, we have to get this right as we refine the map via the challenge process."

The new funding was allocated by last year’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which set up the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program to help more Americans get online. An agency called the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) will distribute funds to states based on how many of their residents lack broadband access.

The money could go to big internet service providers such as Comcast or Spectrum to help them build out connections to new neighborhoods and homes, but it can also be directed to smaller providers, private/public partnerships, and cooperatives, including municipal broadband projects. Any project that receives money from the states will be required to provide an affordable option for low-income households.

The FCC wants to first target “unserved,” communities that don’t have widespread access to at least 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload speeds. (That’s enough to stream a movie in 4K, and conduct Zoom calls.) Next on the priority list are “underserved” areas where many residents can’t sign up for 100/20 Mbps, or faster, service.

These speeds are based on an internet provider’s maximum advertised speeds, not the speeds people actually experience in their homes.

States Say FCC Broadband Map Overstates Coverage

The FCC gave states an early look at the addresses in its database. In October, the Vermont Department of Public Service sent a letter to the FCC, alleging, in part, that the FCC map omitted 22 percent of the addresses in the state’s own records database.

Once the map was released on November 18, Vermont Community Broadband Board, a state agency, started reviewing the FCC map’s information on broadband access throughout Vermont. The agency says it is finding errors.

Vermont estimates that 18.6 percent of its residents lack access to the high-speed internet, while the FCC estimates that the number is just 3 percent. The gap could cost the state millions in funding, officials worry.

"From our initial analysis, we feel that wireless coverage in particular is vastly overstated," says Rob Fish, deputy director at the VCBB, in part because it doesn’t take into account mountains, trees, and other obstructions that block transmission in many locations. He also says the board is checking the map’s claim that many people with slow DSL internet are receiving 25/3 Mbps speeds. The map also shows coverage in locations where ISPs don’t currently offer high-speed service but say they will soon. In many of those neighborhoods, he says, “evidence being gathered on the ground may suggest a different story."

New York is also challenging the new map, based on street-level data collected by its ConnectALL Office. The state submitted more than 31,000 addresses that it says are missing from the FCC map, but which meet the agency’s definition of unserved or underserved households.

A spokesperson for ConnectAll tells CR the office is reviewing FCC map data to determine what additional reviews or challenges should be made. "In the meantime, we are encouraging New Yorkers to check the FCC’s broadband map to confirm that their home and business information is accurate,” she says.

States and consumers have a short window—only until Jan. 13, 2023—for filing challenges before NTIA uses the input to make any revisions to the map, and then start announcing its first funding decisions this summer. As an added obstacle, some states say that restrictive contracts they’ve signed with broadband data suppliers for their own maps could prevent them from providing strong evidence of mistakes to the FCC.

A spokesman for the the NTIA, the agency administering the funding, says that while the new map will be used "as a baseline for allocating broadband funding," it will also consider state-developed maps and additional data to make its final funding decisions.

The FCC says it will update the map every six months based on new data provided by ISPs, consumers, states governments, and community organizations.

How to Check and Challenge the FCC Broadband Map

The information in the map is being provided by internet service providers. To see if you agree with what they’ve told the FCC, you can check the FCC national broadband map yourself. Type in your address and the national map will zoom in to your neighborhood, which will be covered with locations with green dots, one for each location where internet service is available. Click on your home, and you’ll see the various options for service.

Challenges can be made on two fronts—address accuracy and service availability. If your address doesn’t appear, you can click on "challenge location." You can also submit a challenge if the map says a company offers service at your location, but it really doesn’t. Click the “availability challenge” button in the same box. That will bring up a form where you can challenge the information.

Scroll down, complete the form, and choose the reason for your challenge from the drop-down list. You can upload files— screenshots, photos, and emails—that support your challenge. You can also write a description of your experience in the form. Once you hit “submit” your claim will be reviewed by the FCC. If accepted, the agency will pass it on to the internet provider. If the ISP disagrees with you, it will contact you and try to resolve the issue. If the issue can’t be resolved, the FCC will decide who’s right—and if you win the challenge, the ISP has to update its availability data on the map within 30 days of the decision.

The FCC’s new online help center is available to provide assistance with the process.

Our own spot checks around the country showed a mixed bag in terms of accuracy. Among my colleagues, most living in the New York City tristate area, the map seemed to be fairly accurate. At my address, the map correctly listed the two wired providers, Optimum and Verizon, that offer service in my town. But it also included T-Mobile’s home wireless service, which isn’t yet available in my area.

The FCC map shows a number of satellite providers for every address we checked or heard about. These services don’t always deliver the minimum 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload speeds set by the FCC as the definition of high-speed internet. They typically rank near the very bottom of CR’s rankings of the best and worst home internet providers, and tend to be more expensive than fixed internet services.

Several people in other regions tell CR that obstructions and other types of interference prevent satellite or wireless services from working at their locations. For example, Laura Barton, who lives in Nesbit, Mississippi, says the map shows satellite provider Space Explorations—better known as SpaceX, which offers the Starlink service—as available in her area. "But Starlink has a waiting list for this area until mid-2023, and isn’t signing up new customers," she says. Barton says her sister, who lives a few houses away, does have Starlink but doesn’t get anywhere near the 100Mbps service claimed.

As for Barton’s own T-Mobile home internet service, she says it regularly clocks in at 8 to 10 Mbps, again below the speed the company advertises.

New York City resident Claire August says that at her address the FCC map lists five satellite companies she’s never heard of. "I tried looking them up, but I couldn’t find two, and the others make you call them to see if they’re available, or to get the specific price and speed they’re offering." It also showed T-Mobile as an option, though it isn’t available in her area.

The FCC says the new map is still a work in progress. "Releasing this early version of the new maps is intended to kickstart an ongoing, iterative process where we are consistently adding new data to improve and refine the maps." FCC chair Jessica Rosenworcel says.

Consumer Reports is an independent, nonprofit organization that works side by side with consumers to create a fairer, safer, and healthier world. CR does not endorse products or services, and does not accept advertising. Copyright © 2022, Consumer Reports, Inc.

Did you find this post inspiring? Let us know by pinning us!