A Deshka River king salmon. © Eric Booton

The Deshka River

Story by Marian Giannulis

It’s not easy to stand out among Alaska’s many famed and beloved rivers, but one stream in the Matanuska-Susitna Valley is of particular importance to both anglers and scientists. The Deshka River is one of southcentral Alaska’s premier sportfishing streams. The river runs approximately 140 miles from its headwaters south of Denali National Park to its confluence with the Susitna River. The Deshka’s remote setting can be accessed by boat and floatplane.

The Deshka River supports all five species of Alaska salmon along with resident rainbow trout, Dolly Varden, and grayling, but it is best known for its king and silver salmon runs. It has regularly generated the greatest king salmon returns in upper Cook Inlet and it supports the largest silver salmon harvest of the west Susitna tributaries. When the king and silver salmon return, this normally quiet, remote river is bustling with boats full of anglers. The gathering of people around the return of salmon is not a new occurrence. The Deshka River is rich with Indigenous history. Its productive waters have long sustained the Dena’ina peoples. There were once extensive Dene settlements that thrived along the Deshka River.

Given its importance to Indigenous peoples and anglers, it’s no surprise that the Deshka River has attracted the attention of scientists as well. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) has operated a weir on the river since 1995 that counts the annual returns of king and silver salmon. The data collected from this weir informs the river’s annual escapement goals. Daily counts of fish also allow area biologists to issue emergency orders in direct response to the number of fish that have returned in real time. There have been many emergency orders limiting and closing fishing for king salmon in recent years, as overall populations have declined. This monitoring and management are critical to ensuring king salmon populations can survive into future generations.

Cook Inletkeeper staff measuring water temperature in a cold-water inflow on the Deshka River. © Cook Inletkeeper

Deshka Weir Data

As scientists investigate what may be contributing to these declines, the Deshka is providing clues. In 2017, Cook Inletkeeper and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began a five-year effort to track water temperatures in the Deshka. The project monitors year-round water temperatures at 62 sites along the river. Their results found temperatures that regularly reached levels that are harmful for salmon. Water temperatures affect all stages of the salmon lifecycle from the survival of eggs to seaward and returning migrations. Warm water temperatures are stressful for salmon and make them vulnerable to disease, predation, and pollution. Extreme temperatures can even cause death.

Adult salmon are stressed by temperatures above 59º. Juvenile salmon have their growth diminished at 55.4º. Water temperatures as high as 76.1º have been recorded in the Deshka in recent years. While the exact cause of the decline of king salmon populations can’t be attributed to one single thing, warming streams are negatively impacting fish.

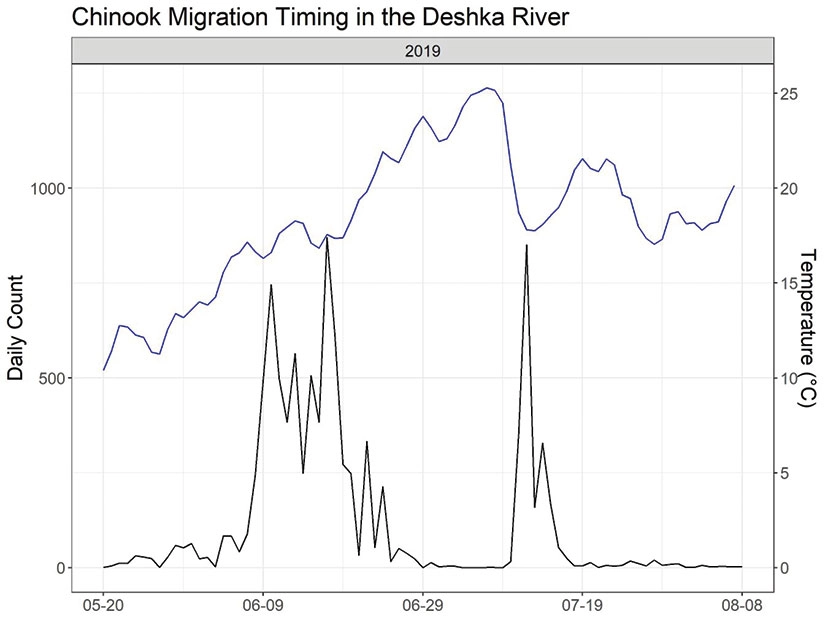

In 2019, adult Chinook (king) salmon altered their migration timing to avoid warm stream temperatures. Chinook count data from ADF&G, water temperature data from Cook Inletkeeper. Graph provided by Rebecca Shaftel, Alaska Center for Conservation Science, UAA.

These stress-inducing warm temperatures are not found consistently throughout the Deshka River. As scientists surveyed temperatures in the river, they found many points of cold-water refugia, which are spots in the river that are persistently cooler than other adjacent areas. These cold-water areas occur when cooler tributaries, springs and groundwater flow into the river. They are also found in deep pools and underneath cut banks and overhanging vegetation. Both juvenile and spawning fish will gather in these areas when water temperatures in other parts of the river reach stressful levels. As water temperatures in streams continue to rise, these areas of cold-water refugia will be increasingly vital to the survival of salmon and resident fish.

Juvenile salmon gathered at a cold-water inflow. © Benjamin Rich

Conservation Decisions

This research has mapped out an important understanding of the Deshka’s habitat. It also gives a glimpse of what is happening in other watersheds across the Mat-Su Valley and Alaska. This information should be considered in management and conservation decisions to ensure the future health of these fisheries. The management of lands immediately adjacent to the Deshka and other significant Susitna rivers are currently in a review process. The Susitna Basin Recreational Rivers Plan was created in 1991 to protect the health of and ensure public access to rivers of significant importance to recreational users. The Susitna Basin Recreation Rivers include Alexander Creek, Deshka River, Lake Creek, Little Susitna River, Talachulitna River, and Talkeetna River. The plan established a mile-wide river corridor around the rivers and developed management guidelines to protect water quantity, water quality, riparian vegetation, wetlands habitat, and more.

By direction of Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy, the plan is currently under review by the Alaska Department of Natural Resources. An advisory board made up of river users and stakeholders are currently reviewing the plan and proposed revisions are anticipated to come soon. The public will have the opportunity to comment on changes and the legislature will have to vote to adopt them.

Whether you love to fish the Deshka, wish to fish there in the future, or care about the health of any of the six aforementioned recreational rivers, you should pay attention to this process and be sure to comment when the proposed revisions are announced. The future plan should continue to allow public access to these incredible rivers and ensure the surrounding lands which provide cold-water refuges are maintained and conserved. The future health of these fish depends on it.

Visit cookinletkeeper.org for more information on stream temperature monitoring, cold-water refugia, and to view the sources referenced in this article.

Trout Unlimited’s mission is to protect, reconnect and restore North America’s coldwater fisheries and their watersheds. Learn about our work in Alaska at tu.org/alaska. Marian Giannulis is the Alaska Communications & Engagement Director for Trout Unlimited.

The post The Deshka River, a Sportfish Haven and Science Subject appeared first on Fish Alaska Magazine.