Being something of a Frenchie wannabe, I tend to don my rose-tinted lunettes when I consider the classic French bistro and its zinc bars and outdoor tables. I mean that quite literally. I can’t help but imagine a single scenario over and over and over again. Me, behind my favorite rose-lensed sunglasses, at a bistro in Paris. Sipping. Laughing. Lingering.

Bistros are the stuff of reveries. Iconic, legendary establishments that exude a certain uncontestable charm. A spell of sorts.

I’m not alone in thinking this. But I also think perhaps the rosiness and romance that tend to envelope bistros comes because I regard everything—the faded decor, the house wine, the passersby, even a mediocre steak frites—a little less critically than usual. Perhaps a large part of my mooniness draws from the fact that I see myself, too, in a less mundane manner. Each time I catch myself in such a moment of fanciful thinking, I see a happier, classier, sassier version of me sitting at that table. France tends to have that effect on people. It takes you back to the moment at hand. And I return to Paris every so often for exactly that. It’s essential.

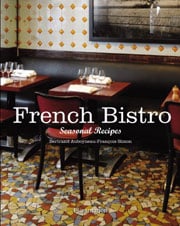

I’d never considered the why behind the bistro effect, but rather just sort of accepted it as fact. Until I flipped through French Bistro, in which Bertrand Auboyneau, owner of the renowned Paul Bert in Paris and founder of the bistronomy movement, shares his insights into the essential components of a proper bistro. He reminds us of the more grounded sturdiness and reliability of the physical bistro which creates the backdrop against which the more chimerical seems possible. You’ll find a soupçon of his thoughts and philosophy below. And fear not. Deconstructing the essential bistro as he does won’t tarnish that rosy tint. If anything, it makes it even rosier. Originally published July 13, 2012.–Renee Schettler Rossi

~~~

The bistro is one of the last remaining venues of live theater in our cities. Clients take their positions without prompting, talk to strangers at the bar, ask their neighbors to pass the salt, scrounge a smoke outside, and maybe even leave with a phone number. The bistro is the setting against which minor dramas and romances are played out. It is a social sanctuary, somewhere to reflect, watch passersby, shrug at calories, and mop up the sauce on our plates with good bread. Let the outside world march on in suits, slaves to their watches. This calm revolt, this rebellion that runs on salted butter, continues to be a success because of its genuine respect for both its food and diners. You will feel it as you enter and taste it in the crunch of the bread.

What defines a bistro? A counter, an owner, and a chef? Limiting the definition to this trio would be too simplistic to describe an entire universe. A bistro comprises much more.

What would a bistro be without its bar? The combined weight of its lead, zinc, and heavy wood anchor it solidly to the floor. It seems to have been there long enough to have grown roots, drawing strength and serenity from its grounded solidity. The bar is subjected to thumps, knocks, and wipes. It is impervious to parting words, endless chatter, bygones being bygones, and slates being wiped clean. It listens with a kindly ear to human suffering and passing fortune. The bar is a benevolent entity, a latter-day confessional. When the time comes and you are ready, you can leave the safety of the bar for the comfort of your table.

Here’s another French paradox. If the food is good, the décor seems spectacular. If the food is disappointing, the décor is filed away as iffy and the service spotty. The bench covered in worn leatherette will seem redolent of the romance of past eras rather than simply shabby. Bistro décor is like traveling back in time to a golden age. There will be exposed brick walls, vintage posters, enamel signage, old tiling, molded ceilings, worn wooden tables, and ancient chairs. They all transmit the same timeless message, like a quaint dialect, somewhat out of date, that reassures us and sets our bellies rumbling.

The bistro chair is nifty and nimble, punctuating the dining space. It takes just a flick of the wrist to spin it. It is multipurpose: it can be straddled and stacked,; it can be sent flying; and it can even crack skulls. The original bistro chair was designed in 1859 in Michael Thonet’s workshop. This ingenious inventor devised a process for bending solid wood into curved shape, and it was the Thonet prototype number 14 that shot to success. The whole world then made knock-offs of his deign, producing chairs that would support the world’ most illustrious posteriors.

The strength of bistro cooking owes much to its flexibility. The chalkboard menu attests to its adaptability. Far more than a rustic decorative feature, the chalkboard reflects the economic preoccupations of a cuisine based on market availability and fluctuating commodity prices. Should a certain fish suddenly become plentiful, the chef and the owner will immediately modify the day’s menu. If a dish’s ingredients are exhausted, it’s erased immediately. The bistro is lucky enough to be able to seize opportunities as they arise, though it must be faithful to its fundamental principles. You go because you’re sure to find your usual steak with mustard, sole meuniere, or favorite dried sausage. The affability is tangible in the down-to-earth dishes, the ones that everyone likes. Upscale restaurants have taken to revisiting bistro recipes, gussying up old standbys. That’s fine. Bistro cooking can take the competition.

France has a dazzling array of bad characters. Just stand at the bar of any bistro. You’re bound to spot one or more clients, unpredictable beings, looking downhearted, sullen, morose, or annoyed. Some of them manage to display the whole range of gloomy emotions from bleakness to wretchedness. Those who enter laughing and jolly are few and far between, and their demeanor raises the suspicion that they have been enjoying their predinner drinks. The success of an evening at a bistro can often hinge on a single client. Just one cantankerous person who loses his or her patience or explodes can quickly ruin the ambience. And this is why bistro owners are so attentive to the diners, keeping them under constant, close surveillance. French clients are unique creatures, and it is in this spirit that they must be welcomed.

The ambience of a bistro is original and inimitable. Myriad conversations, the clinking of cutlery, waiters overacting their roles, barked-out orders, spoons tinkling against coffee cups, a cork popping out of a bottle all come together in a life-affirming babble. A general state of well-being resonates.