In the animated series BoJack Horseman, anthropomorphic animals live alongside human characters in a society rife with hedonism, egotism and self-destructive behaviour. The world of ancient Egyptian deities is similar in more ways than one.

The hit American series, produced between 2014 and 2020, and now streaming on Netflix, was named for its lead character, an over-the-hill television star with a man’s body and horse’s head.

As a PhD candidate researching iconography in ancient Egypt, I am often struck by the manner in which BoJack Horseman and Egyptian iconography - the products of two very different cultures - have arrived at similar solutions in their portrayal of anthropomorphic beings.

In both cases, anthropomorphic animals of various species are portrayed with a certain uniformity. Characters could also be rendered zoomorphically, depending on their role in a given scene.

Horus and Horseman

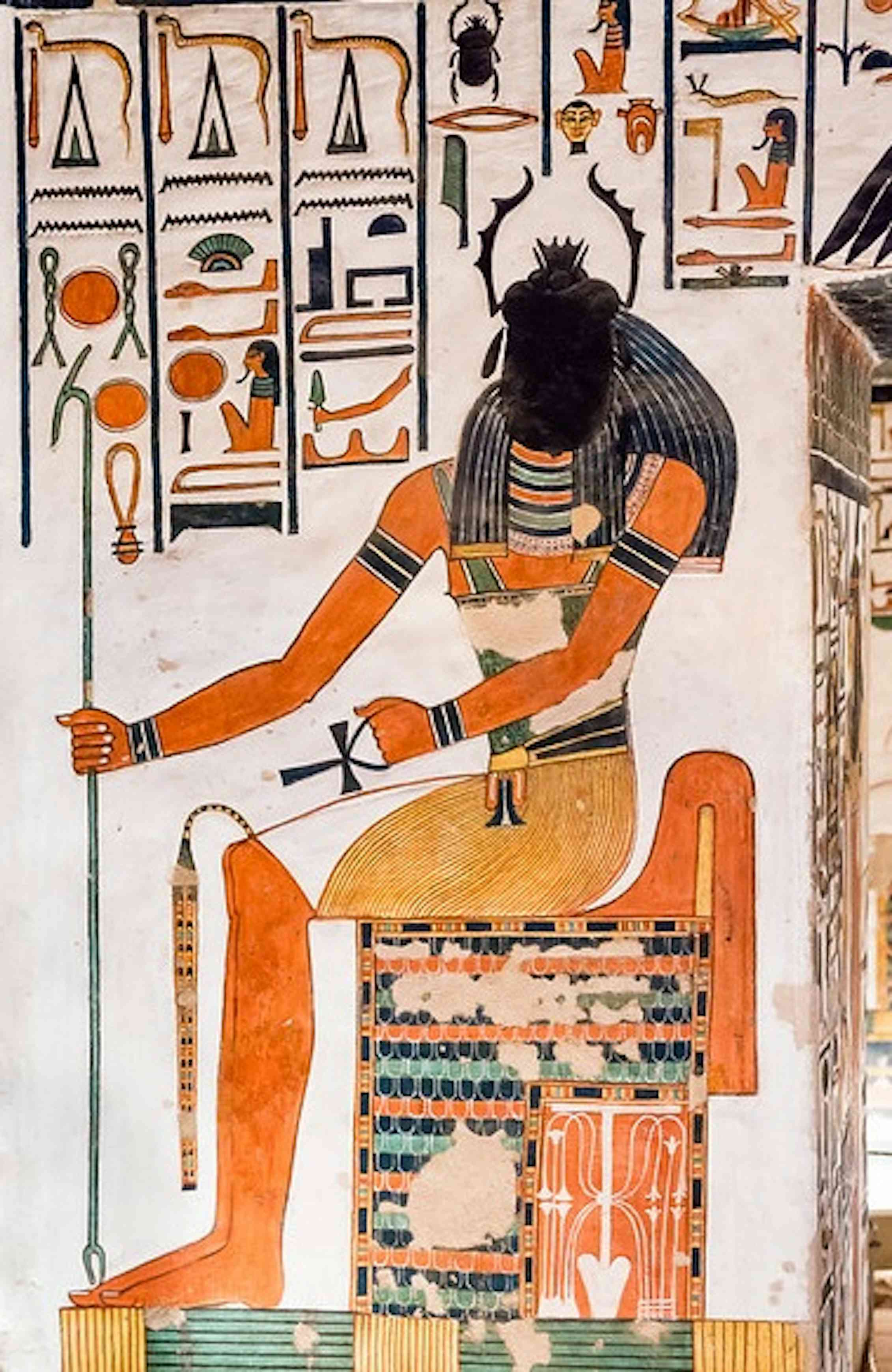

Depictions of animal-headed gods can be found as early as the Second Dynasty of Egypt (about 2890 – 2686 BCE). Today, images such as the falcon-headed Horus and the crocodile-headed Sobek have become emblematic of Egyptian civilization. However, these examples are merely one of the many ways that Egyptian deities were represented.

The goddess Hathor, for instance, could be represented either as a cow, a bovine-headed woman or a woman with large bovine ears. Generally, the manifestation assumed by a deity is dependent on the scene’s context. This notion can be better explained through the artistic style of BoJack Horseman.

Although the characters of BoJack Horseman are made up of a diverse range of species, they share several common traits. There is a standardization of scale: the titulary character, a horse, stands at roughly the same height as Mr. Peanutbutter (a Labrador Retriever) and Officer Meow Meow Fuzzyface (a cat). Most characters are entirely human below the neck: birds, for example, have arms that flap like wings in flight.

These idiosyncrasies add to the show’s comedic effect, but they are also crucial to its coherence and progression. The creatures of BoJack Horseman occupy the same world, where they travel in the same vehicles and dine with the same utensils. This uniformity in character design is what enables a horse, a fish and a human to interact seamlessly.

Similarly, Egyptian deities are frequently depicted in direct interaction with a human figure. A common example is where a god receives cultic offerings from the pharaoh. A zoomorphic depiction here could limit the deity’s ability to grasp objects, or to make gestures that are key to the symbolism of the scene.

Ancient Egyptian artists also placed great emphasis on balance and proportions. Rendering all figures in an upright posture provides visual symmetry.

Two legs better?

The form assumed by the deities also depends on their function in a given scene. The god Anubis, in his role as the protector of tombs, is typically represented as a reclining canine that resembles the African golden wolf. This manifestation serves to underline the animal’s territorial behaviour. Conversely, when Anubis is tasked with a role that requires human dexterity (such as the weighing of the deceased’s heart), he is usually rendered as an anthropomorphic canine.

The same flexibility can be observed in BoJack Horseman. Like other characters in the show, the defining traits of Princess Carolyn - an earnest and career-driven cat - are very much human. In times of emergency, however, she calls upon the agility and nimbleness of a feline. To the audience, this transition becomes perceptible when she stops walking upright and begins moving on all fours.

Khepri and Apep

A key aspect of Egyptian art is that each entity tends to be depicted in its most characteristic view, without foreshortening or other modifications familiar to western traditions. For example, ancient Egyptians depicted human figures using an amalgamation of viewpoints: the eye is rendered in full view, the shoulders are depicted from a frontal perspective and the feet are largely in profile.

For many animal species, the most characteristic body part is the head, which is often sufficient for the purpose of identification. Insects, however, are typically too small for their heads to be readily identifiable.

Khepri, the god whose head is represented as a full-sized beetle, reflects the reality that for human observers, a top-down view of the beetle presents a recognizable image. If you are familiar with emojis, you might have noted that insects and other arthropods are often rendered in full; whereas a cat or lion can be represented by their faces.

Although anthropomorphism is found across various cultures, it is a treatment rarely afforded to insects. The Egyptian preoccupation with the scarab beetle stems from its habit of rolling a ball of dung, which is evocative of the sun’s rising.

In BoJack Horseman, insect characters are relatively rare, and they tend to have distinctive bodily features. In one episode, a praying mantis is shown with its characteristic forearms. The scene implies the female is preparing for sexual cannibalism, a behaviour common among many mantis species. If the mantis was depicted with human forearms, the intimations would likely have been lost.

The artists of BoJack Horseman and ancient Egypt depict anthropomorphic snakes in a similar manner, by replacing the human head with the slender, upper body of a snake rearing upwards. Proportionally, the result is not ideal — snake deities such as Apep are depicted with a spindly head far outsized by a headdress. Nevertheless, such depictions show a snake in its defensive stance, a characteristic and memorable image. If the artists had rendered only the snake’s head, it could easily be confused with other reptiles.

Divine nature

Ultimately, the richness of the Egyptian pantheon is a result of astute observations and spirited imagination. For its devotees, this grounding in the natural world meant that the divine figures are easy to identify with.

And just like the protagonists of BoJack Horseman, Egyptian gods can be flawed in ways that are strikingly human. In a legend of Hathor, the blood-thirsty goddess was set on destroying all mankind, until she was unwittingly tricked into consuming a pool of red-coloured beer.

As Mr. Peanutbutter might have said, such stories would make for a decent crossover.

Jun Yi Wong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Did you find this article inspiring? PIN this to your board on Pinterest!