They said I was a terrible auctioneer. But it wasn’t my fault. Really.

I was shocked and embarrassed. What could I say? Arguing would have been unproductive. I was only there to offer my estate sale services.

When I told the homeowners that their cherished goods were worth a fraction of the amount they expected, they didn’t believe me. I “must be wrong,” they said. I “must be a terrible auctioneer” to not know the value of what they owned.

Of course, if they had planned better or started sooner, they would have understood. There are planning tools available, but they didn’t know about them, and I was too upset to remember.

I’ll tell you about those later.

Their children didn’t want any of their stuff. Consignment shops refused to take the bulk of it. In today’s tech-heavy, mobile, Ikea-centric Millennial world, formal furniture and outdated decor are no longer wanted.

I should have known better. I should have taken a different approach. After all, I painfully learned this lesson in 2002, when my mother died: Your children won’t want most of your stuff.

Was I an ungrateful child?

I didn’t want much of my mother’s stuff, either. A few days after her funeral, my siblings and I – all five of us – gathered at Mom’s house to discuss what to do with her hard-earned possessions.

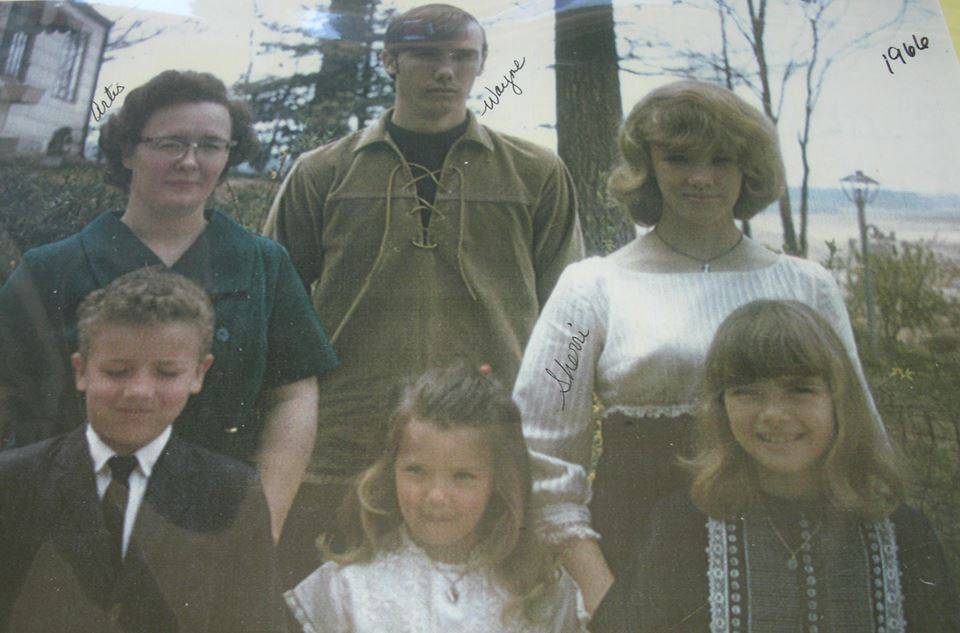

Hard-earned, indeed. My father was killed in a car accident in 1966. He was 34 years old and left a wife and five kids from six to sixteen. I was the oldest. My Mom went to secretarial school and got a job with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Each of us contributed according to our ability and shared according to our needs.

For the next twenty years, Mom collected Ethan Allen furniture. One piece at a time, as she could afford it, she filled the house with Early American, nutmeg-colored maple furniture. The tables had round legs, the upholstered chairs were wing-backs, and the wooden chairs were reproduction Windsors.

Fast-forward to 2002. The five of us had families and full houses. We were in the Digital Age. As we walked through Mom’s house, the conversation was:

“Do you want this television?”

“No, I don’t want it. I have three.”

“I think you should take this dining room set.”

“What would I do with it? I have a house full of furniture.”

“How about these movies?”

“They are VHS. They won’t work on my new DVD player.”

You get the point. The household goods were a non-starter. No one wanted Early American Maple furniture, or pots and pans, or open-edition framed prints. After the walk-through, my youngest sister chimed in: “Mom said this would happen. She said we weren’t going to want most of this stuff. That’s why she put stickers on the things she wanted us to have.”

So there was a plan, after all. Whenever one of us expressed an interest in an item, Mom put a sticker on the bottom with our name on it. I got the box of family photos and the ceremonial flag from my father’s burial at Arlington National Cemetery. But my brother wanted the photos as well. I agreed to scan them all and share them on a disc. Two sisters wanted the Christmas decorations, and they agreed to share them.

We kept the memorabilia. We kept the memories. The rest we gave away. We allowed extended family members to take whatever they wanted. We donated the rest to a local church’s charity shop.

Too much stuff

You see, we Baby Boomers just have too much stuff. Our grandparents raised families during the Great Depression. Our parents compensated for a childhood of want by saving everything “for a rainy day.” We Boomers grew up in an expanding economy with a glut of consumer goods. Our houses are full.

Take a look around the room you are in at the moment. Look at each item and ask: “Who would want this when I’m gone? If no one wants it, who will be responsible for getting rid of it? Who will take it?”

A Mother’s Day gift to sons and daughters

As they grow, your children become attached to objects and traditions. Everything has a story. This Mother’s Day, when family members gather, tell some of those stories. Look at a souvenir, and share memories of the vacation where it was purchased. Pass around a photo album, and laugh at crazy fashion choices and hair-dos. Pick up each item in your collection and tell a story about it. Let your children ask questions. If you can’t entertain (not many of us can in the Spring of 2020), share online. Talk on the phone.

When you’re gone, your children will cherish the memories of your life together. Objects trigger memories. They weave generations together. That’s why they are called heirlooms.

The way to ensure that items go where you want them to go is to have a “who gets what” conversation with your family. You don’t have to make firm decisions, but you must open the conversation. Your family won’t broach the subject. No one wants to talk about Mom dying. Having a “distribution” conversation is your gift to them.

I promised to tell you about the distribution planning tools. Here are a couple of my favorites:

The University of Minnesota offers a workbook to help families make a distribution plan. It’s titled Who Gets Grandma’s Yellow Pie Plate: a Guide to Passing on Personal Possessions. Details on how to get this workbook are available here. If you would like to start building a catalog of your dearest possessions, have a look at WorthPoint’s Vault. It’s currently in beta testing, but it’s not too soon to have a look.

Wayne Jordan is WorthPoint’s Senior Editor. He is the author of four books: The Business of Antiques published by Krause Books, Antique Mall Profits for Dealers and Dabblers, Consignment Gold Rush: the Ultimate Startup Guide and Relocate for Less published by Learning Curve Books. He is a regular contributor to a variety of antiques trade publications. He blogs at sellmoreantiques.net.

WorthPoint—Discover Your Hidden Wealth®